One of the most important principles of object oriented programming – delimiting internal interface from the external one.

That is “a must” practice in developing anything more complex than a “hello world” app.

To understand this, let’s break away from development and turn our eyes into the real world.

Usually, devices that we’re using are quite complex. But delimiting the internal interface from the external one allows to use them without problems.

For instance, a coffee machine. Simple from outside: a button, a display, a few holes…And, surely, the result – great coffee! :)

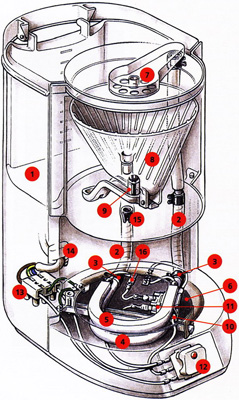

But inside… (a picture from the repair manual)

A lot of details. But we can use it without knowing anything.

Coffee machines are quite reliable, aren’t they? We can use one for years, and only if something goes wrong – bring it for repairs.

The secret of reliability and simplicity of a coffee machine – all details are well-tuned and hidden inside.

If we remove the protective cover from the coffee machine, then using it will be much more complex (where to press?), and dangerous (it can electrocute).

As we’ll see, in programming objects are like coffee machines.

But in order to hide inner details, we’ll use not a protective cover, but rather special syntax of the language and conventions.

In object-oriented programming, properties and methods are split into two groups:

Internal interface – methods and properties, accessible from other methods of the class, but not from the outside.

External interface – methods and properties, accessible also from outside the class.

If we continue the analogy with the coffee machine – what’s hidden inside: a boiler tube, heating element, and so on – is its internal interface.

An internal interface is used for the object to work, its details use each other. For instance, a boiler tube is attached to the heating element.

But from the outside a coffee machine is closed by the protective cover, so that no one can reach those. Details are hidden and inaccessible. We can use its features via the external interface.

So, all we need to use an object is to know its external interface. We may be completely unaware how it works inside, and that’s great.

That was a general introduction.

In JavaScript, there are two types of object fields (properties and methods):

Public: accessible from anywhere. They comprise the external interface. Until now we were only using public properties and methods.

Private: accessible only from inside the class. These are for the internal interface.

In many other languages there also exist “protected” fields: accessible only from inside the class and those extending it (like private, but plus access from inheriting classes). They are also useful for the internal interface. They are in a sense more widespread than private ones, because we usually want inheriting classes to gain access to them.

Protected fields are not implemented in JavaScript on the language level, but in practice they are very convenient, so they are emulated.

Now we’ll make a coffee machine in JavaScript with all these types of properties. A coffee machine has a lot of details, we won’t model them to stay simple (though we could).

Let’s make a simple coffee machine class first:

class CoffeeMachine {

waterAmount = 0; // the amount of water inside

constructor(power) {

this.power = power;

alert( `Created a coffee-machine, power: ${power}` );

}

}

// create the coffee machine

let coffeeMachine = new CoffeeMachine(100);

// add water

coffeeMachine.waterAmount = 200;Right now the properties waterAmount and power are public. We can easily get/set them from the outside to any value.

Let’s change waterAmount property to protected to have more control over it. For instance, we don’t want anyone to set it below zero.

Protected properties are usually prefixed with an underscore _.

That is not enforced on the language level, but there’s a well-known convention between programmers that such properties and methods should not be accessed from the outside.

So our property will be called _waterAmount:

class CoffeeMachine {

_waterAmount = 0;

set waterAmount(value) {

if (value < 0) {

value = 0;

}

this._waterAmount = value;

}

get waterAmount() {

return this._waterAmount;

}

constructor(power) {

this._power = power;

}

}

// create the coffee machine

let coffeeMachine = new CoffeeMachine(100);

// add water

coffeeMachine.waterAmount = -10; // _waterAmount will become 0, not -10Now the access is under control, so setting the water amount below zero becomes impossible.

For power property, let’s make it read-only. It sometimes happens that a property must be set at creation time only, and then never modified.

That’s exactly the case for a coffee machine: power never changes.

To do so, we only need to make getter, but not the setter:

class CoffeeMachine {

// ...

constructor(power) {

this._power = power;

}

get power() {

return this._power;

}

}

// create the coffee machine

let coffeeMachine = new CoffeeMachine(100);

alert(`Power is: ${coffeeMachine.power}W`); // Power is: 100W

coffeeMachine.power = 25; // Error (no setter)Getter/setter functions

Here we used getter/setter syntax.

But most of the time get.../set... functions are preferred, like this:

class CoffeeMachine {

_waterAmount = 0;

setWaterAmount(value) {

if (value < 0) value = 0;

this._waterAmount = value;

}

getWaterAmount() {

return this._waterAmount;

}

}

new CoffeeMachine().setWaterAmount(100);That looks a bit longer, but functions are more flexible. They can accept multiple arguments (even if we don’t need them right now).

On the other hand, get/set syntax is shorter, so ultimately there’s no strict rule, it’s up to you to decide.

Protected fields are inherited

If we inherit class MegaMachine extends CoffeeMachine, then nothing prevents us from accessing this._waterAmount or this._power from the methods of the new class.

So protected fields are naturally inheritable. Unlike private ones that we’ll see below.

A recent addition

This is a recent addition to the language. Not supported in JavaScript engines, or supported partially yet, requires polyfilling.

There’s a finished JavaScript proposal, almost in the standard, that provides language-level support for private properties and methods.

Privates should start with #. They are only accessible from inside the class.

For instance, here’s a private #waterLimit property and the water-checking private method #fixWaterAmount:

class CoffeeMachine {

#waterLimit = 200;

#fixWaterAmount(value) {

if (value < 0) return 0;

if (value > this.#waterLimit) return this.#waterLimit;

}

setWaterAmount(value) {

this.#waterLimit = this.#fixWaterAmount(value);

}

}

let coffeeMachine = new CoffeeMachine();

// can't access privates from outside of the class

coffeeMachine.#fixWaterAmount(123); // Error

coffeeMachine.#waterLimit = 1000; // ErrorOn the language level, # is a special sign that the field is private. We can’t access it from outside or from inheriting classes.

Private fields do not conflict with public ones. We can have both private #waterAmount and public waterAmount fields at the same time.

For instance, let’s make waterAmount an accessor for #waterAmount:

class CoffeeMachine {

#waterAmount = 0;

get waterAmount() {

return this.#waterAmount;

}

set waterAmount(value) {

if (value < 0) value = 0;

this.#waterAmount = value;

}

}

let machine = new CoffeeMachine();

machine.waterAmount = 100;

alert(machine.#waterAmount); // ErrorUnlike protected ones, private fields are enforced by the language itself. That’s a good thing.

But if we inherit from CoffeeMachine, then we’ll have no direct access to #waterAmount. We’ll need to rely on waterAmount getter/setter:

class MegaCoffeeMachine extends CoffeeMachine {

method() {

alert( this.#waterAmount ); // Error: can only access from CoffeeMachine

}

}In many scenarios such limitation is too severe. If we extend a CoffeeMachine, we may have legitimate reasons to access its internals. That’s why protected fields are used more often, even though they are not supported by the language syntax.

Private fields are not available as this[name]

Private fields are special.

As we know, usually we can access fields using this[name]:

class User {

...

sayHi() {

let fieldName = "name";

alert(`Hello, ${this[fieldName]}`);

}

}With private fields that’s impossible: this['#name'] doesn’t work. That’s a syntax limitation to ensure privacy.

In terms of OOP, delimiting of the internal interface from the external one is called encapsulation.

It gives the following benefits:

Protection for users, so that they don’t shoot themselves in the foot

Imagine, there’s a team of developers using a coffee machine. It was made by the “Best CoffeeMachine” company, and works fine, but a protective cover was removed. So the internal interface is exposed.

All developers are civilized – they use the coffee machine as intended. But one of them, John, decided that he’s the smartest one, and made some tweaks in the coffee machine internals. So the coffee machine failed two days later.

That’s surely not John’s fault, but rather the person who removed the protective cover and let John do his manipulations.

The same in programming. If a user of a class will change things not intended to be changed from the outside – the consequences are unpredictable.

Supportable

The situation in programming is more complex than with a real-life coffee machine, because we don’t just buy it once. The code constantly undergoes development and improvement.

If we strictly delimit the internal interface, then the developer of the class can freely change its internal properties and methods, even without informing the users.

If you’re a developer of such class, it’s great to know that private methods can be safely renamed, their parameters can be changed, and even removed, because no external code depends on them.

For users, when a new version comes out, it may be a total overhaul internally, but still simple to upgrade if the external interface is the same.

Hiding complexity

People adore using things that are simple. At least from outside. What’s inside is a different thing.

Programmers are not an exception.

It’s always convenient when implementation details are hidden, and a simple, well-documented external interface is available.

To hide an internal interface we use either protected or private properties:

Protected fields start with _. That’s a well-known convention, not enforced at the language level. Programmers should only access a field starting with _ from its class and classes inheriting from it.

Private fields start with #. JavaScript makes sure we can only access those from inside the class.

Right now, private fields are not well-supported among browsers, but can be polyfilled.