A lightweight, object-oriented state machine implementation in Python with many extensions. Compatible with Python 2.7+ and 3.0+.

pip install transitions

... or clone the repo from GitHub and then:

python setup.py install

They say a good example is worth 100 pages of API documentation, a million directives, or a thousand words.

Well, "they" probably lie... but here's an example anyway:

from transitions import Machine

import random

class NarcolepticSuperhero(object):

# Define some states. Most of the time, narcoleptic superheroes are just like

# everyone else. Except for...

states = ['asleep', 'hanging out', 'hungry', 'sweaty', 'saving the world']

def __init__(self, name):

# No anonymous superheroes on my watch! Every narcoleptic superhero gets

# a name. Any name at all. SleepyMan. SlumberGirl. You get the idea.

self.name = name

# What have we accomplished today?

self.kittens_rescued = 0

# Initialize the state machine

self.machine = Machine(model=self, states=NarcolepticSuperhero.states, initial='asleep')

# Add some transitions. We could also define these using a static list of

# dictionaries, as we did with states above, and then pass the list to

# the Machine initializer as the transitions= argument.

# At some point, every superhero must rise and shine.

self.machine.add_transition(trigger='wake_up', source='asleep', dest='hanging out')

# Superheroes need to keep in shape.

self.machine.add_transition('work_out', 'hanging out', 'hungry')

# Those calories won't replenish themselves!

self.machine.add_transition('eat', 'hungry', 'hanging out')

# Superheroes are always on call. ALWAYS. But they're not always

# dressed in work-appropriate clothing.

self.machine.add_transition('distress_call', '*', 'saving the world',

before='change_into_super_secret_costume')

# When they get off work, they're all sweaty and disgusting. But before

# they do anything else, they have to meticulously log their latest

# escapades. Because the legal department says so.

self.machine.add_transition('complete_mission', 'saving the world', 'sweaty',

after='update_journal')

# Sweat is a disorder that can be remedied with water.

# Unless you've had a particularly long day, in which case... bed time!

self.machine.add_transition('clean_up', 'sweaty', 'asleep', conditions=['is_exhausted'])

self.machine.add_transition('clean_up', 'sweaty', 'hanging out')

# Our NarcolepticSuperhero can fall asleep at pretty much any time.

self.machine.add_transition('nap', '*', 'asleep')

def update_journal(self):

""" Dear Diary, today I saved Mr. Whiskers. Again. """

self.kittens_rescued += 1

@property

def is_exhausted(self):

""" Basically a coin toss. """

return random.random() < 0.5

def change_into_super_secret_costume(self):

print("Beauty, eh?")There, now you've baked a state machine into NarcolepticSuperhero. Let's take him/her/it out for a spin...

>>> batman = NarcolepticSuperhero("Batman")

>>> batman.state

'asleep'

>>> batman.wake_up()

>>> batman.state

'hanging out'

>>> batman.nap()

>>> batman.state

'asleep'

>>> batman.clean_up()

MachineError: "Can't trigger event clean_up from state asleep!"

>>> batman.wake_up()

>>> batman.work_out()

>>> batman.state

'hungry'

# Batman still hasn't done anything useful...

>>> batman.kittens_rescued

0

# We now take you live to the scene of a horrific kitten entreement...

>>> batman.distress_call()

'Beauty, eh?'

>>> batman.state

'saving the world'

# Back to the crib.

>>> batman.complete_mission()

>>> batman.state

'sweaty'

>>> batman.clean_up()

>>> batman.state

'asleep' # Too tired to shower!

# Another productive day, Alfred.

>>> batman.kittens_rescued

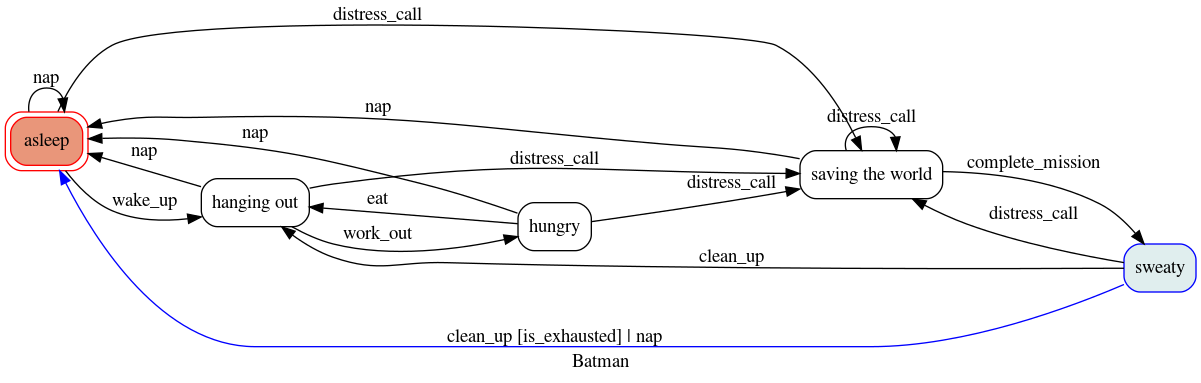

1While we cannot read the mind of the actual batman, we surely can visualize the current state of our NarcolepticSuperhero.

Have a look at the Diagrams extensions if you want to know how.

A state machine is a model of behavior composed of a finite number of states and transitions between those states. Within each state and transition some action can be performed. A state machine needs to start at some initial state. When using transitions, a state machine may consist of multiple objects where some (machines) contain definitions for the manipulation of other (models). Below, we will look at some core concepts and how to work with them.

State. A state represents a particular condition or stage in the state machine. It's a distinct mode of behavior or phase in a process.

Transition. This is the process or event that causes the state machine to change from one state to another.

Model. The actual stateful structure. It's the entity that gets updated during transitions. It may also define actions that will be executed during transitions. For instance, right before a transition or when a state is entered or exited.

Machine. This is the entity that manages and controls the model, states, transitions, and actions. It's the conductor that orchestrates the entire process of the state machine.

Trigger. This is the event that initiates a transition, the method that sends the signal to start a transition.

Action. Specific operation or task that is performed when a certain state is entered, exited, or during a transition. The action is implemented through callbacks, which are functions that get executed when some event happens.

Getting a state machine up and running is pretty simple. Let's say you have the object lump (an instance of class Matter), and you want to manage its states:

class Matter(object):

pass

lump = Matter()You can initialize a (minimal) working state machine bound to the model lump like this:

from transitions import Machine

machine = Machine(model=lump, states=['solid', 'liquid', 'gas', 'plasma'], initial='solid')

# Lump now has a new state attribute!

lump.state

>>> 'solid'An alternative is to not explicitly pass a model to the Machine initializer:

machine = Machine(states=['solid', 'liquid', 'gas', 'plasma'], initial='solid')

# The machine instance itself now acts as a model

machine.state

>>> 'solid'Note that this time I did not pass the lump model as an argument. The first argument passed to Machine acts as a model. So when I pass something there, all the convenience functions will be added to the object. If no model is provided then the machine instance itself acts as a model.

When at the beginning I said "minimal", it was because while this state machine is technically operational, it doesn't actually do anything. It starts in the 'solid' state, but won't ever move into another state, because no transitions are defined... yet!

Let's try again.

# The states

states=['solid', 'liquid', 'gas', 'plasma']

# And some transitions between states. We're lazy, so we'll leave out

# the inverse phase transitions (freezing, condensation, etc.).

transitions = [

{ 'trigger': 'melt', 'source': 'solid', 'dest': 'liquid' },

{ 'trigger': 'evaporate', 'source': 'liquid', 'dest': 'gas' },

{ 'trigger': 'sublimate', 'source': 'solid', 'dest': 'gas' },

{ 'trigger': 'ionize', 'source': 'gas', 'dest': 'plasma' }

]

# Initialize

machine = Machine(lump, states=states, transitions=transitions, initial='liquid')

# Now lump maintains state...

lump.state

>>> 'liquid'

# And that state can change...

# Either calling the shiny new trigger methods

lump.evaporate()

lump.state

>>> 'gas'

# Or by calling the trigger method directly

lump.trigger('ionize')

lump.state

>>> 'plasma'Notice the shiny new methods attached to the Matter instance (evaporate(), ionize(), etc.).

Each method triggers the corresponding transition.

Transitions can also be triggered dynamically by calling the trigger() method provided with the name of the transition, as shown above.

More on this in the Triggering a transition section.

The soul of any good state machine (and of many bad ones, no doubt) is a set of states. Above, we defined the valid model states by passing a list of strings to the Machine initializer. But internally, states are actually represented as State objects.

You can initialize and modify States in a number of ways. Specifically, you can:

Machine initializer giving the name(s) of the state(s), orState object, orThe following snippets illustrate several ways to achieve the same goal:

# import Machine and State class

from transitions import Machine, State

# Create a list of 3 states to pass to the Machine

# initializer. We can mix types; in this case, we

# pass one State, one string, and one dict.

states = [

State(name='solid'),

'liquid',

{ 'name': 'gas'}

]

machine = Machine(lump, states)

# This alternative example illustrates more explicit

# addition of states and state callbacks, but the net

# result is identical to the above.

machine = Machine(lump)

solid = State('solid')

liquid = State('liquid')

gas = State('gas')

machine.add_states([solid, liquid, gas])States are initialized once when added to the machine and will persist until they are removed from it. In other words: if you alter the attributes of a state object, this change will NOT be reset the next time you enter that state. Have a look at how to extend state features in case you require some other behaviour.

But just having states and being able to move around between them (transitions) isn't very useful by itself. What if you want to do something, perform some action when you enter or exit a state? This is where callbacks come in.

A State can also be associated with a list of enter and exit callbacks, which are called whenever the state machine enters or leaves that state. You can specify callbacks during initialization by passing them to a State object constructor, in a state property dictionary, or add them later.

For convenience, whenever a new State is added to a Machine, the methods on_enter_«state name» and on_exit_«state name» are dynamically created on the Machine (not on the model!), which allow you to dynamically add new enter and exit callbacks later if you need them.

# Our old Matter class, now with a couple of new methods we

# can trigger when entering or exit states.

class Matter(object):

def say_hello(self): print("hello, new state!")

def say_goodbye(self): print("goodbye, old state!")

lump = Matter()

# Same states as above, but now we give StateA an exit callback

states = [

State(name='solid', on_exit=['say_goodbye']),

'liquid',

{ 'name': 'gas', 'on_exit': ['say_goodbye']}

]

machine = Machine(lump, states=states)

machine.add_transition('sublimate', 'solid', 'gas')

# Callbacks can also be added after initialization using

# the dynamically added on_enter_ and on_exit_ methods.

# Note that the initial call to add the callback is made

# on the Machine and not on the model.

machine.on_enter_gas('say_hello')

# Test out the callbacks...

machine.set_state('solid')

lump.sublimate()

>>> 'goodbye, old state!'

>>> 'hello, new state!'Note that on_enter_«state name» callback will not fire when a Machine is first initialized. For example if you have an on_enter_A() callback defined, and initialize the Machine with initial='A', on_enter_A() will not be fired until the next time you enter state A. (If you need to make sure on_enter_A() fires at initialization, you can simply create a dummy initial state and then explicitly call to_A() inside the __init__ method.)

In addition to passing in callbacks when initializing a State, or adding them dynamically, it's also possible to define callbacks in the model class itself, which may increase code clarity. For example:

class Matter(object):

def say_hello(self): print("hello, new state!")

def say_goodbye(self): print("goodbye, old state!")

def on_enter_A(self): print("We've just entered state A!")

lump = Matter()

machine = Machine(lump, states=['A', 'B', 'C'])Now, any time lump transitions to state A, the on_enter_A() method defined in the Matter class will fire.

You can make use of on_final callbacks which will be triggered when a state with final=True is entered.

from transitions import Machine, State

states = [State(name='idling'),

State(name='rescuing_kitten'),

State(name='offender_gone', final=True),

State(name='offender_caught', final=True)]

transitions = [["called", "idling", "rescuing_kitten"], # we will come when called

{"trigger": "intervene",

"source": "rescuing_kitten",

"dest": "offender_gone", # we

"conditions": "offender_is_faster"}, # unless they are faster

["intervene", "rescuing_kitten", "offender_caught"]]

class FinalSuperhero(object):

def __init__(self, speed):

self.machine = Machine(self, states=states, transitions=transitions, initial="idling", on_final="claim_success")

self.speed = speed

def offender_is_faster(self, offender_speed):

return self.speed < offender_speed

def claim_success(self, **kwargs):

print("The kitten is safe.")

hero = FinalSuperhero(speed=10) # we are not in shape today

hero.called()

assert hero.is_rescuing_kitten()

hero.intervene(offender_speed=15)

# >>> 'The kitten is safe'

assert hero.machine.get_state(hero.state).final # it's over

assert hero.is_offender_gone() # maybe next time ...You can always check the current state of the model by either:

.state attribute, oris_«state name»()

And if you want to retrieve the actual State object for the current state, you can do that through the Machine instance's get_state() method.

lump.state

>>> 'solid'

lump.is_gas()

>>> False

lump.is_solid()

>>> True

machine.get_state(lump.state).name

>>> 'solid'If you'd like you can choose your own state attribute name by passing the model_attribute argument while initializing the Machine. This will also change the name of is_«state name»() to is_«model_attribute»_«state name»() though. Similarly, auto transitions will be named to_«model_attribute»_«state name»() instead of to_«state name»(). This is done to allow multiple machines to work on the same model with individual state attribute names.

lump = Matter()

machine = Machine(lump, states=['solid', 'liquid', 'gas'], model_attribute='matter_state', initial='solid')

lump.matter_state

>>> 'solid'

# with a custom 'model_attribute', states can also be checked like this:

lump.is_matter_state_solid()

>>> True

lump.to_matter_state_gas()

>>> TrueSo far we have seen how we can give state names and use these names to work with our state machine. If you favour stricter typing and more IDE code completion (or you just can't type 'sesquipedalophobia' any longer because the word scares you) using Enumerations might be what you are looking for:

import enum # Python 2.7 users need to have 'enum34' installed

from transitions import Machine

class States(enum.Enum):

ERROR = 0

RED = 1

YELLOW = 2

GREEN = 3

transitions = [['proceed', States.RED, States.YELLOW],

['proceed', States.YELLOW, States.GREEN],

['error', '*', States.ERROR]]

m = Machine(states=States, transitions=transitions, initial=States.RED)

assert m.is_RED()

assert m.state is States.RED

state = m.get_state(States.RED) # get transitions.State object

print(state.name) # >>> RED

m.proceed()

m.proceed()

assert m.is_GREEN()

m.error()

assert m.state is States.ERRORYou can mix enums and strings if you like (e.g. [States.RED, 'ORANGE', States.YELLOW, States.GREEN]) but note that internally, transitions will still handle states by name (enum.Enum.name).

Thus, it is not possible to have the states 'GREEN' and States.GREEN at the same time.

Some of the above examples already illustrate the use of transitions in passing, but here we'll explore them in more detail.

As with states, each transition is represented internally as its own object – an instance of class Transition. The quickest way to initialize a set of transitions is to pass a dictionary, or list of dictionaries, to the Machine initializer. We already saw this above:

transitions = [

{ 'trigger': 'melt', 'source': 'solid', 'dest': 'liquid' },

{ 'trigger': 'evaporate', 'source': 'liquid', 'dest': 'gas' },

{ 'trigger': 'sublimate', 'source': 'solid', 'dest': 'gas' },

{ 'trigger': 'ionize', 'source': 'gas', 'dest': 'plasma' }

]

machine = Machine(model=Matter(), states=states, transitions=transitions)Defining transitions in dictionaries has the benefit of clarity, but can be cumbersome. If you're after brevity, you might choose to define transitions using lists. Just make sure that the elements in each list are in the same order as the positional arguments in the Transition initialization (i.e., trigger, source, destination, etc.).

The following list-of-lists is functionally equivalent to the list-of-dictionaries above:

transitions = [

['melt', 'solid', 'liquid'],

['evaporate', 'liquid', 'gas'],

['sublimate', 'solid', 'gas'],

['ionize', 'gas', 'plasma']

]Alternatively, you can add transitions to a Machine after initialization:

machine = Machine(model=lump, states=states, initial='solid')

machine.add_transition('melt', source='solid', dest='liquid')For a transition to be executed, some event needs to trigger it. There are two ways to do this:

Using the automatically attached method in the base model:

>>> lump.melt()

>>> lump.state

'liquid'

>>> lump.evaporate()

>>> lump.state

'gas'Note how you don't have to explicitly define these methods anywhere; the name of each transition is bound to the model passed to the Machine initializer (in this case, lump). This also means that your model should not already contain methods with the same name as event triggers since transitions will only attach convenience methods to your model if the spot is not already taken. If you want to modify that behaviour, have a look at the FAQ.

Using the trigger method, now attached to your model (if it hasn't been there before). This method lets you execute transitions by name in case dynamic triggering is required:

>>> lump.trigger('melt')

>>> lump.state

'liquid'

>>> lump.trigger('evaporate')

>>> lump.state

'gas'By default, triggering an invalid transition will raise an exception:

>>> lump.to_gas()

>>> # This won't work because only objects in a solid state can melt

>>> lump.melt()

transitions.core.MachineError: "Can't trigger event melt from state gas!"This behavior is generally desirable, since it helps alert you to problems in your code. But in some cases, you might want to silently ignore invalid triggers. You can do this by setting ignore_invalid_triggers=True (either on a state-by-state basis, or globally for all states):

>>> # Globally suppress invalid trigger exceptions

>>> m = Machine(lump, states, initial='solid', ignore_invalid_triggers=True)

>>> # ...or suppress for only one group of states

>>> states = ['new_state1', 'new_state2']

>>> m.add_states(states, ignore_invalid_triggers=True)

>>> # ...or even just for a single state. Here, exceptions will only be suppressed when the current state is A.

>>> states = [State('A', ignore_invalid_triggers=True), 'B', 'C']

>>> m = Machine(lump, states)

>>> # ...this can be inverted as well if just one state should raise an exception

>>> # since the machine's global value is not applied to a previously initialized state.

>>> states = ['A', 'B', State('C')] # the default value for 'ignore_invalid_triggers' is False

>>> m = Machine(lump, states, ignore_invalid_triggers=True)If you need to know which transitions are valid from a certain state, you can use get_triggers:

m.get_triggers('solid')

>>> ['melt', 'sublimate']

m.get_triggers('liquid')

>>> ['evaporate']

m.get_triggers('plasma')

>>> []

# you can also query several states at once

m.get_triggers('solid', 'liquid', 'gas', 'plasma')

>>> ['melt', 'evaporate', 'sublimate', 'ionize']If you have followed this documentation from the beginning, you will notice that get_triggers actually returns more triggers than the explicitly defined ones shown above, such as to_liquid and so on.

These are called auto-transitions and will be introduced in the next section.

In addition to any transitions added explicitly, a to_«state»() method is created automatically whenever a state is added to a Machine instance. This method transitions to the target state no matter which state the machine is currently in:

lump.to_liquid()

lump.state

>>> 'liquid'

lump.to_solid()

lump.state

>>> 'solid'If you desire, you can disable this behavior by setting auto_transitions=False in the Machine initializer.

A given trigger can be attached to multiple transitions, some of which can potentially begin or end in the same state. For example:

machine.add_transition('transmogrify', ['solid', 'liquid', 'gas'], 'plasma')

machine.add_transition('transmogrify', 'plasma', 'solid')

# This next transition will never execute

machine.add_transition('transmogrify', 'plasma', 'gas')In this case, calling transmogrify() will set the model's state to 'solid' if it's currently 'plasma', and set it to 'plasma' otherwise. (Note that only the first matching transition will execute; thus, the transition defined in the last line above won't do anything.)

You can also make a trigger cause a transition from all states to a particular destination by using the '*' wildcard:

machine.add_transition('to_liquid', '*', 'liquid')Note that wildcard transitions will only apply to states that exist at the time of the add_transition() call. Calling a wildcard-based transition when the model is in a state added after the transition was defined will elicit an invalid transition message, and will not transition to the target state.

A reflexive trigger (trigger that has the same state as source and destination) can easily be added specifying = as destination.

This is handy if the same reflexive trigger should be added to multiple states.

For example:

machine.add_transition('touch', ['liquid', 'gas', 'plasma'], '=', after='change_shape')This will add reflexive transitions for all three states with touch() as trigger and with change_shape executed after each trigger.

In contrast to reflexive transitions, internal transitions will never actually leave the state.

This means that transition-related callbacks such as before or after will be processed while state-related callbacks exit or enter will not.

To define a transition to be internal, set the destination to None.

machine.add_transition('internal', ['liquid', 'gas'], None, after='change_shape')A common desire is for state transitions to follow a strict linear sequence. For instance, given states ['A', 'B', 'C'], you might want valid transitions for A → B, B → C, and C → A (but no other pairs).

To facilitate this behavior, Transitions provides an add_ordered_transitions() method in the Machine class:

states = ['A', 'B', 'C']

# See the "alternative initialization" section for an explanation of the 1st argument to init

machine = Machine(states=states, initial='A')

machine.add_ordered_transitions()

machine.next_state()

print(machine.state)

>>> 'B'

# We can also define a different order of transitions

machine = Machine(states=states, initial='A')

machine.add_ordered_transitions(['A', 'C', 'B'])

machine.next_state()

print(machine.state)

>>> 'C'

# Conditions can be passed to 'add_ordered_transitions' as well

# If one condition is passed, it will be used for all transitions

machine = Machine(states=states, initial='A')

machine.add_ordered_transitions(conditions='check')

# If a list is passed, it must contain exactly as many elements as the

# machine contains states (A->B, ..., X->A)

machine = Machine(states=states, initial='A')

machine.add_ordered_transitions(conditions=['check_A2B', ..., 'check_X2A'])

# Conditions are always applied starting from the initial state

machine = Machine(states=states, initial='B')

machine.add_ordered_transitions(conditions=['check_B2C', ..., 'check_A2B'])

# With `loop=False`, the transition from the last state to the first state will be omitted (e.g. C->A)

# When you also pass conditions, you need to pass one condition less (len(states)-1)

machine = Machine(states=states, initial='A')

machine.add_ordered_transitions(loop=False)

machine.next_state()

machine.next_state()

machine.next_state() # transitions.core.MachineError: "Can't trigger event next_state from state C!"The default behaviour in Transitions is to process events instantly. This means events within an on_enter method will be processed before callbacks bound to after are called.

def go_to_C():

global machine

machine.to_C()

def after_advance():

print("I am in state B now!")

def entering_C():

print("I am in state C now!")

states = ['A', 'B', 'C']

machine = Machine(states=states, initial='A')

# we want a message when state transition to B has been completed

machine.add_transition('advance', 'A', 'B', after=after_advance)

# call transition from state B to state C

machine.on_enter_B(go_to_C)

# we also want a message when entering state C

machine.on_enter_C(entering_C)

machine.advance()

>>> 'I am in state C now!'

>>> 'I am in state B now!' # what?The execution order of this example is

prepare -> before -> on_enter_B -> on_enter_C -> after.

If queued processing is enabled, a transition will be finished before the next transition is triggered:

machine = Machine(states=states, queued=True, initial='A')

...

machine.advance()

>>> 'I am in state B now!'

>>> 'I am in state C now!' # That's better!This results in

prepare -> before -> on_enter_B -> queue(to_C) -> after -> on_enter_C.

Important note: when processing events in a queue, the trigger call will always return True, since there is no way to determine at queuing time whether a transition involving queued calls will ultimately complete successfully. This is true even when only a single event is processed.

machine.add_transition('jump', 'A', 'C', conditions='will_fail')

...

# queued=False

machine.jump()

>>> False

# queued=True

machine.jump()

>>> TrueWhen a model is removed from the machine, transitions will also remove all related events from the queue.

class Model:

def on_enter_B(self):

self.to_C() # add event to queue ...

self.machine.remove_model(self) # aaaand it's goneSometimes you only want a particular transition to execute if a specific condition occurs. You can do this by passing a method, or list of methods, in the conditions argument:

# Our Matter class, now with a bunch of methods that return booleans.

class Matter(object):

def is_flammable(self): return False

def is_really_hot(self): return True

machine.add_transition('heat', 'solid', 'gas', conditions='is_flammable')

machine.add_transition('heat', 'solid', 'liquid', conditions=['is_really_hot'])In the above example, calling heat() when the model is in state 'solid' will transition to state 'gas' if is_flammable returns True. Otherwise, it will transition to state 'liquid' if is_really_hot returns True.

For convenience, there's also an 'unless' argument that behaves exactly like conditions, but inverted:

machine.add_transition('heat', 'solid', 'gas', unless=['is_flammable', 'is_really_hot'])In this case, the model would transition from solid to gas whenever heat() fires, provided that both is_flammable() and is_really_hot() return False.

Note that condition-checking methods will passively receive optional arguments and/or data objects passed to triggering methods. For instance, the following call:

lump.heat(temp=74)

# equivalent to lump.trigger('heat', temp=74)... would pass the temp=74 optional kwarg to the is_flammable() check (possibly wrapped in an EventData instance). For more on this, see the Passing data section below.

If you want to make sure a transition is possible before you go ahead with it, you can use the may_<trigger_name> functions that have been added to your model.

Your model also contains the may_trigger function to check a trigger by name:

# check if the current temperature is hot enough to trigger a transition

if lump.may_heat():

# if lump.may_trigger("heat"):

lump.heat()This will execute all prepare callbacks and evaluate the conditions assigned to the potential transitions.

Transition checks can also be used when a transition's destination is not available (yet):

machine.add_transition('elevate', 'solid', 'spiritual')

assert not lump.may_elevate() # not ready yet :(

assert not lump.may_trigger("elevate") # same result for checks via trigger nameYou can attach callbacks to transitions as well as states. Every transition has 'before' and 'after' attributes that contain a list of methods to call before and after the transition executes:

class Matter(object):

def make_hissing_noises(self): print("HISSSSSSSSSSSSSSSS")

def disappear(self): print("where'd all the liquid go?")

transitions = [

{ 'trigger': 'melt', 'source': 'solid', 'dest': 'liquid', 'before': 'make_hissing_noises'},

{ 'trigger': 'evaporate', 'source': 'liquid', 'dest': 'gas', 'after': 'disappear' }

]

lump = Matter()

machine = Machine(lump, states, transitions=transitions, initial='solid')

lump.melt()

>>> "HISSSSSSSSSSSSSSSS"

lump.evaporate()

>>> "where'd all the liquid go?"There is also a 'prepare' callback that is executed as soon as a transition starts, before any 'conditions' are checked or other callbacks are executed.

class Matter(object):

heat = False

attempts = 0

def count_attempts(self): self.attempts += 1

def heat_up(self): self.heat = random.random() < 0.25

def stats(self): print('It took you %i attempts to melt the lump!' %self.attempts)

@property

def is_really_hot(self):

return self.heat

states=['solid', 'liquid', 'gas', 'plasma']

transitions = [

{ 'trigger': 'melt', 'source': 'solid', 'dest': 'liquid', 'prepare': ['heat_up', 'count_attempts'], 'conditions': 'is_really_hot', 'after': 'stats'},

]

lump = Matter()

machine = Machine(lump, states, transitions=transitions, initial='solid')

lump.melt()

lump.melt()

lump.melt()

lump.melt()

>>> "It took you 4 attempts to melt the lump!"Note that prepare will not be called unless the current state is a valid source for the named transition.

Default actions meant to be executed before or after every transition can be passed to Machine during initialization with

before_state_change and after_state_change respectively:

class Matter(object):

def make_hissing_noises(self): print("HISSSSSSSSSSSSSSSS")

def disappear(self): print("where'd all the liquid go?")

states=['solid', 'liquid', 'gas', 'plasma']

lump = Matter()

m = Machine(lump, states, before_state_change='make_hissing_noises', after_state_change='disappear')

lump.to_gas()

>>> "HISSSSSSSSSSSSSSSS"

>>> "where'd all the liquid go?"There are also two keywords for callbacks which should be executed independently a) of how many transitions are possible,

b) if any transition succeeds and c) even if an error is raised during the execution of some other callback.

Callbacks passed to Machine with prepare_event will be executed once before processing possible transitions

(and their individual prepare callbacks) takes place.

Callbacks of finalize_event will be executed regardless of the success of the processed transitions.

Note that if an error occurred it will be attached to event_data as error and can be retrieved with send_event=True.

from transitions import Machine

class Matter(object):

def raise_error(self, event): raise ValueError("Oh no")

def prepare(self, event): print("I am ready!")

def finalize(self, event): print("Result: ", type(event.error), event.error)

states=['solid', 'liquid', 'gas', 'plasma']

lump = Matter()

m = Machine(lump, states, prepare_event='prepare', before_state_change='raise_error',

finalize_event='finalize', send_event=True)

try:

lump.to_gas()

except ValueError:

pass

print(lump.state)

# >>> I am ready!

# >>> Result: <class 'ValueError'> Oh no

# >>> initialSometimes things just don't work out as intended and we need to handle exceptions and clean up the mess to keep things going.

We can pass callbacks to on_exception to do this:

from transitions import Machine

class Matter(object):

def raise_error(self, event): raise ValueError("Oh no")

def handle_error(self, event):

print("Fixing things ...")

del event.error # it did not happen if we cannot see it ...

states=['solid', 'liquid', 'gas', 'plasma']

lump = Matter()

m = Machine(lump, states, before_state_change='raise_error', on_exception='handle_error', send_event=True)

try:

lump.to_gas()

except ValueError:

pass

print(lump.state)

# >>> Fixing things ...

# >>> initialAs you have probably already realized, the standard way of passing callables to states, conditions and transitions is by name. When processing callbacks and conditions, transitions will use their name to retrieve the related callable from the model. If the method cannot be retrieved and it contains dots, transitions will treat the name as a path to a module function and try to import it. Alternatively, you can pass names of properties or attributes. They will be wrapped into functions but cannot receive event data for obvious reasons. You can also pass callables such as (bound) functions directly. As mentioned earlier, you can also pass lists/tuples of callables names to the callback parameters. Callbacks will be executed in the order they were added.

from transitions import Machine

from mod import imported_func

import random

class Model(object):

def a_callback(self):

imported_func()

@property

def a_property(self):

""" Basically a coin toss. """

return random.random() < 0.5

an_attribute = False

model = Model()

machine = Machine(model=model, states=['A'], initial='A')

machine.add_transition('by_name', 'A', 'A', conditions='a_property', after='a_callback')

machine.add_transition('by_reference', 'A', 'A', unless=['a_property', 'an_attribute'], after=model.a_callback)

machine.add_transition('imported', 'A', 'A', after='mod.imported_func')

model.by_name()

model.by_reference()

model.imported()The callable resolution is done in Machine.resolve_callable.

This method can be overridden in case more complex callable resolution strategies are required.

Example

class CustomMachine(Machine):

@staticmethod

def resolve_callable(func, event_data):

# manipulate arguments here and return func, or super() if no manipulation is done.

super(CustomMachine, CustomMachine).resolve_callable(func, event_data)In summary, there are currently three ways to trigger events. You can call a model's convenience functions like lump.melt(),

execute triggers by name such as lump.trigger("melt") or dispatch events on multiple models with machine.dispatch("melt")

(see section about multiple models in alternative initialization patterns).

Callbacks on transitions are then executed in the following order:

| Callback | Current State | Comments |

|---|---|---|

'machine.prepare_event' |

source |

executed once before individual transitions are processed |

'transition.prepare' |

source |

executed as soon as the transition starts |

'transition.conditions' |

source |

conditions may fail and halt the transition |

'transition.unless' |

source |

conditions may fail and halt the transition |

'machine.before_state_change' |

source |

default callbacks declared on model |

'transition.before' |

source |

|

'state.on_exit' |

source |

callbacks declared on the source state |

<STATE CHANGE> |

||

'state.on_enter' |

destination |

callbacks declared on the destination state |

'transition.after' |

destination |

|

'machine.on_final' |

destination |

callbacks on children will be called first |

'machine.after_state_change' |

destination |

default callbacks declared on model; will also be called after internal transitions |

'machine.on_exception' |

source/destination |

callbacks will be executed when an exception has been raised |

'machine.finalize_event' |

source/destination |

callbacks will be executed even if no transition took place or an exception has been raised |

If any callback raises an exception, the processing of callbacks is not continued. This means that when an error occurs before the transition (in state.on_exit or earlier), it is halted. In case there is a raise after the transition has been conducted (in state.on_enter or later), the state change persists and no rollback is happening. Callbacks specified in machine.finalize_event will always be executed unless the exception is raised by a finalizing callback itself. Note that each callback sequence has to be finished before the next stage is executed. Blocking callbacks will halt the execution order and therefore block the trigger or dispatch call itself. If you want callbacks to be executed in parallel, you could have a look at the extensions AsyncMachine for asynchronous processing or LockedMachine for threading.

Sometimes you need to pass the callback functions registered at machine initialization some data that reflects the model's current state. Transitions allows you to do this in two different ways.

First (the default), you can pass any positional or keyword arguments directly to the trigger methods (created when you call add_transition()):

class Matter(object):

def __init__(self): self.set_environment()

def set_environment(self, temp=0, pressure=101.325):

self.temp = temp

self.pressure = pressure

def print_temperature(self): print("Current temperature is %d degrees celsius." % self.temp)

def print_pressure(self): print("Current pressure is %.2f kPa." % self.pressure)

lump = Matter()

machine = Machine(lump, ['solid', 'liquid'], initial='solid')

machine.add_transition('melt', 'solid', 'liquid', before='set_environment')

lump.melt(45) # positional arg;

# equivalent to lump.trigger('melt', 45)

lump.print_temperature()

>>> 'Current temperature is 45 degrees celsius.'

machine.set_state('solid') # reset state so we can melt again

lump.melt(pressure=300.23) # keyword args also work

lump.print_pressure()

>>> 'Current pressure is 300.23 kPa.'You can pass any number of arguments you like to the trigger.

There is one important limitation to this approach: every callback function triggered by the state transition must be able to handle all of the arguments. This may cause problems if the callbacks each expect somewhat different data.

To get around this, Transitions supports an alternate method for sending data. If you set send_event=True at Machine initialization, all arguments to the triggers will be wrapped in an EventData instance and passed on to every callback. (The EventData object also maintains internal references to the source state, model, transition, machine, and trigger associated with the event, in case you need to access these for anything.)

class Matter(object):

def __init__(self):

self.temp = 0

self.pressure = 101.325

# Note that the sole argument is now the EventData instance.

# This object stores positional arguments passed to the trigger method in the

# .args property, and stores keywords arguments in the .kwargs dictionary.

def set_environment(self, event):

self.temp = event.kwargs.get('temp', 0)

self.pressure = event.kwargs.get('pressure', 101.325)

def print_pressure(self): print("Current pressure is %.2f kPa." % self.pressure)

lump = Matter()

machine = Machine(lump, ['solid', 'liquid'], send_event=True, initial='solid')

machine.add_transition('melt', 'solid', 'liquid', before='set_environment')

lump.melt(temp=45, pressure=1853.68) # keyword args

lump.print_pressure()

>>> 'Current pressure is 1853.68 kPa.'In all of the examples so far, we've attached a new Machine instance to a separate model (lump, an instance of class Matter). While this separation keeps things tidy (because you don't have to monkey patch a whole bunch of new methods into the Matter class), it can also get annoying, since it requires you to keep track of which methods are called on the state machine, and which ones are called on the model that the state machine is bound to (e.g., lump.on_enter_StateA() vs. machine.add_transition()).

Fortunately, Transitions is flexible, and supports two other initialization patterns.

First, you can create a standalone state machine that doesn't require another model at all. Simply omit the model argument during initialization:

machine = Machine(states=states, transitions=transitions, initial='solid')

machine.melt()

machine.state

>>> 'liquid'If you initialize the machine this way, you can then attach all triggering events (like evaporate(), sublimate(), etc.) and all callback functions directly to the Machine instance.

This approach has the benefit of consolidating all of the state machine functionality in one place, but can feel a little bit unnatural if you think state logic should be contained within the model itself rather than in a separate controller.

An alternative (potentially better) approach is to have the model inherit from the Machine class. Transitions is designed to support inheritance seamlessly. (just be sure to override class Machine's __init__ method!):

class Matter(Machine):

def say_hello(self): print("hello, new state!")

def say_goodbye(self): print("goodbye, old state!")

def __init__(self):

states = ['solid', 'liquid', 'gas']

Machine.__init__(self, states=states, initial='solid')

self.add_transition('melt', 'solid', 'liquid')

lump = Matter()

lump.state

>>> 'solid'

lump.melt()

lump.state

>>> 'liquid'Here you get to consolidate all state machine functionality into your existing model, which often feels more natural than sticking all of the functionality we want in a separate standalone Machine instance.

A machine can handle multiple models which can be passed as a list like Machine(model=[model1, model2, ...]).

In cases where you want to add models as well as the machine instance itself, you can pass the class variable placeholder (string) Machine.self_literal during initialization like Machine(model=[Machine.self_literal, model1, ...]).

You can also create a standalone machine, and register models dynamically via machine.add_model by passing model=None to the constructor.

Furthermore, you can use machine.dispatch to trigger events on all currently added models.

Remember to call machine.remove_model if machine is long-lasting and your models are temporary and should be garbage collected:

class Matter():

pass

lump1 = Matter()

lump2 = Matter()

# setting 'model' to None or passing an empty list will initialize the machine without a model

machine = Machine(model=None, states=states, transitions=transitions, initial='solid')

machine.add_model(lump1)

machine.add_model(lump2, initial='liquid')

lump1.state

>>> 'solid'

lump2.state

>>> 'liquid'

# custom events as well as auto transitions can be dispatched to all models

machine.dispatch("to_plasma")

lump1.state

>>> 'plasma'

assert lump1.state == lump2.state

machine.remove_model([lump1, lump2])

del lump1 # lump1 is garbage collected

del lump2 # lump2 is garbage collectedIf you don't provide an initial state in the state machine constructor, transitions will create and add a default state called 'initial'.

If you do not want a default initial state, you can pass initial=None.

However, in this case you need to pass an initial state every time you add a model.

machine = Machine(model=None, states=states, transitions=transitions, initial=None)

machine.add_model(Matter())

>>> "MachineError: No initial state configured for machine, must specify when adding model."

machine.add_model(Matter(), initial='liquid')Models with multiple states could attach multiple machines using different model_attribute values. As mentioned in Checking state, this will add custom is/to_<model_attribute>_<state_name> functions:

lump = Matter()

matter_machine = Machine(lump, states=['solid', 'liquid', 'gas'], initial='solid')

# add a second machine to the same model but assign a different state attribute

shipment_machine = Machine(lump, states=['delivered', 'shipping'], initial='delivered', model_attribute='shipping_state')

lump.state

>>> 'solid'

lump.is_solid() # check the default field

>>> True

lump.shipping_state

>>> 'delivered'

lump.is_shipping_state_delivered() # check the custom field.

>>> True

lump.to_shipping_state_shipping()

>>> True

lump.is_shipping_state_delivered()

>>> FalseTransitions includes very rudimentary logging capabilities. A number of events – namely, state changes, transition triggers, and conditional checks – are logged as INFO-level events using the standard Python logging module. This means you can easily configure logging to standard output in a script:

# Set up logging; The basic log level will be DEBUG

import logging

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.DEBUG)

# Set transitions' log level to INFO; DEBUG messages will be omitted

logging.getLogger('transitions').setLevel(logging.INFO)

# Business as usual

machine = Machine(states=states, transitions=transitions, initial='solid')

...Machines are picklable and can be stored and loaded with pickle. For Python 3.3 and earlier dill is required.

import dill as pickle # only required for Python 3.3 and earlier

m = Machine(states=['A', 'B', 'C'], initial='A')

m.to_B()

m.state

>>> B

# store the machine

dump = pickle.dumps(m)

# load the Machine instance again

m2 = pickle.loads(dump)

m2.state

>>> B

m2.states.keys()

>>> ['A', 'B', 'C']As you probably noticed, transitions uses some of Python's dynamic features to give you handy ways to handle models. However, static type checkers don't like model attributes and methods not being known before runtime. Historically, transitions also didn't assign convenience methods already defined on models to prevent accidental overrides.

But don't worry! You can use the machine constructor parameter model_override to change how models are decorated. If you set model_override=True, transitions will only override already defined methods. This prevents new methods from showing up at runtime and also allows you to define which helper methods you want to use.

from transitions import Machine

# Dynamic assignment

class Model:

pass

model = Model()

default_machine = Machine(model, states=["A", "B"], transitions=[["go", "A", "B"]], initial="A")

print(model.__dict__.keys()) # all convenience functions have been assigned

# >> dict_keys(['trigger', 'to_A', 'may_to_A', 'to_B', 'may_to_B', 'go', 'may_go', 'is_A', 'is_B', 'state'])

assert model.is_A() # Unresolved attribute reference 'is_A' for class 'Model'

# Predefined assigment: We are just interested in calling our 'go' event and will trigger the other events by name

class PredefinedModel:

# state (or another parameter if you set 'model_attribute') will be assigned anyway

# because we need to keep track of the model's state

state: str

def go(self) -> bool:

raise RuntimeError("Should be overridden!")

def trigger(self, trigger_name: str) -> bool:

raise RuntimeError("Should be overridden!")

model = PredefinedModel()

override_machine = Machine(model, states=["A", "B"], transitions=[["go", "A", "B"]], initial="A", model_override=True)

print(model.__dict__.keys())

# >> dict_keys(['trigger', 'go', 'state'])

model.trigger("to_B")

assert model.state == "B"If you want to use all the convenience functions and throw some callbacks into the mix, defining a model can get pretty complicated when you have a lot of states and transitions defined.

The method generate_base_model in transitions can generate a base model from a machine configuration to help you out with that.

from transitions.experimental.utils import generate_base_model

simple_config = {

"states": ["A", "B"],

"transitions": [

["go", "A", "B"],

],

"initial": "A",

"before_state_change": "call_this",

"model_override": True,

}

class_definition = generate_base_model(simple_config)

with open("base_model.py", "w") as f:

f.write(class_definition)

# ... in another file

from transitions import Machine

from base_model import BaseModel

class Model(BaseModel): # call_this will be an abstract method in BaseModel

def call_this(self) -> None:

# do something

model = Model()

machine = Machine(model, **simple_config)Defining model methods that will be overridden adds a bit of extra work.

It might be cumbersome to switch back and forth to make sure event names are spelled correctly, especially if states and transitions are defined in lists before or after your model. You can cut down on the boilerplate and the uncertainty of working with strings by defining states as enums. You can also define transitions right in your model class with the help of add_transitions and event.

It's up to you whether you use the function decorator add_transitions or event to assign values to attributes depends on your preferred code style.

They both work the same way, have the same signature, and should result in (almost) the same IDE type hints.

As this is still a work in progress, you'll need to create a custom Machine class and use with_model_definitions for transitions to check for transitions defined that way.

from enum import Enum

from transitions.experimental.utils import with_model_definitions, event, add_transitions, transition

from transitions import Machine

class State(Enum):

A = "A"

B = "B"

C = "C"

class Model:

state: State = State.A

@add_transitions(transition(source=State.A, dest=State.B), [State.C, State.A])

@add_transitions({"source": State.B, "dest": State.A})

def foo(self): ...

bar = event(

{"source": State.B, "dest": State.A, "conditions": lambda: False},

transition(source=State.B, dest=State.C)

)

@with_model_definitions # don't forget to define your model with this decorator!

class MyMachine(Machine):

pass

model = Model()

machine = MyMachine(model, states=State, initial=model.state)

model.foo()

model.bar()

assert model.state == State.C

model.foo()

assert model.state == State.AEven though the core of transitions is kept lightweight, there are a variety of MixIns to extend its functionality. Currently supported are:

There are two mechanisms to retrieve a state machine instance with the desired features enabled.

The first approach makes use of the convenience factory with the four parameters graph, nested, locked or asyncio set to True if the feature is required:

from transitions.extensions import MachineFactory

# create a machine with mixins

diagram_cls = MachineFactory.get_predefined(graph=True)

nested_locked_cls = MachineFactory.get_predefined(nested=True, locked=True)

async_machine_cls = MachineFactory.get_predefined(asyncio=True)

# create instances from these classes

# instances can be used like simple machines

machine1 = diagram_cls(model, state, transitions)

machine2 = nested_locked_cls(model, state, transitions)This approach targets experimental use since in this case the underlying classes do not have to be known.

However, classes can also be directly imported from transitions.extensions. The naming scheme is as follows:

| Diagrams | Nested | Locked | Asyncio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machine | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ |

| GraphMachine | ✓ | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ |

| HierarchicalMachine | ✘ | ✓ | ✘ | ✘ |

| LockedMachine | ✘ | ✘ | ✓ | ✘ |

| HierarchicalGraphMachine | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ | ✘ |

| LockedGraphMachine | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ | ✘ |

| LockedHierarchicalMachine | ✘ | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ |

| LockedHierarchicalGraphMachine | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ |

| AsyncMachine | ✘ | ✘ | ✘ | ✓ |

| AsyncGraphMachine | ✓ | ✘ | ✘ | ✓ |

| HierarchicalAsyncMachine | ✘ | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ |

| HierarchicalAsyncGraphMachine | ✓ | ✓ | ✘ | ✓ |

To use a feature-rich state machine, one could write:

from transitions.extensions import LockedHierarchicalGraphMachine as LHGMachine

machine = LHGMachine(model, states, transitions)Transitions includes an extension module which allows nesting states.

This allows us to create contexts and to model cases where states are related to certain subtasks in the state machine.

To create a nested state, either import NestedState from transitions or use a dictionary with the initialization arguments name and children.

Optionally, initial can be used to define a sub state to transit to, when the nested state is entered.

from transitions.extensions import HierarchicalMachine

states = ['standing', 'walking', {'name': 'caffeinated', 'children':['dithering', 'running']}]

transitions = [

['walk', 'standing', 'walking'],

['stop', 'walking', 'standing'],

['drink', '*', 'caffeinated'],

['walk', ['caffeinated', 'caffeinated_dithering'], 'caffeinated_running'],

['relax', 'caffeinated', 'standing']

]

machine = HierarchicalMachine(states=states, transitions=transitions, initial='standing', ignore_invalid_triggers=True)

machine.walk() # Walking now

machine.stop() # let's stop for a moment

machine.drink() # coffee time

machine.state

>>> 'caffeinated'

machine.walk() # we have to go faster

machine.state

>>> 'caffeinated_running'

machine.stop() # can't stop moving!

machine.state

>>> 'caffeinated_running'

machine.relax() # leave nested state

machine.state # phew, what a ride

>>> 'standing'

# machine.on_enter_caffeinated_running('callback_method')A configuration making use of initial could look like this:

# ...

states = ['standing', 'walking', {'name': 'caffeinated', 'initial': 'dithering', 'children': ['dithering', 'running']}]

transitions = [

['walk', 'standing', 'walking'],

['stop', 'walking', 'standing'],

# this transition will end in 'caffeinated_dithering'...

['drink', '*', 'caffeinated'],

# ... that is why we do not need do specify 'caffeinated' here anymore

['walk', 'caffeinated_dithering', 'caffeinated_running'],

['relax', 'caffeinated', 'standing']

]

# ...The initial keyword of the HierarchicalMachine constructor accepts nested states (e.g. initial='caffeinated_running') and a list of states which is considered to be a parallel state (e.g. initial=['A', 'B']) or the current state of another model (initial=model.state) which should be effectively one of the previous mentioned options. Note that when passing a string, transition will check the targeted state for initial substates and use this as an entry state. This will be done recursively until a substate does not mention an initial state. Parallel states or a state passed as a list will be used 'as is' and no further initial evaluation will be conducted.

Note that your previously created state object must be a NestedState or a derived class of it.

The standard State class used in simple Machine instances lacks features required for nesting.

from transitions.extensions.nesting import HierarchicalMachine, NestedState

from transitions import State

m = HierarchicalMachine(states=['A'], initial='initial')

m.add_state('B') # fine

m.add_state({'name': 'C'}) # also fine

m.add_state(NestedState('D')) # fine as well

m.add_state(State('E')) # does not work!Some things that have to be considered when working with nested states: State names are concatenated with NestedState.separator.

Currently the separator is set to underscore ('_') and therefore behaves similar to the basic machine.

This means a substate bar from state foo will be known by foo_bar. A substate baz of bar will be referred to as foo_bar_baz and so on.

When entering a substate, enter will be called for all parent states. The same is true for exiting substates.

Third, nested states can overwrite transition behaviour of their parents.

If a transition is not known to the current state it will be delegated to its parent.

This means that in the standard configuration, state names in HSMs MUST NOT contain underscores.

For transitions it's impossible to tell whether machine.add_state('state_name') should add a state named state_name or add a substate name to the state state.

In some cases this is not sufficient however.

For instance if state names consist of more than one word and you want/need to use underscore to separate them instead of CamelCase.

To deal with this, you can change the character used for separation quite easily.

You can even use fancy unicode characters if you use Python 3.

Setting the separator to something else than underscore changes some of the behaviour (auto_transition and setting callbacks) though:

from transitions.extensions import HierarchicalMachine

from transitions.extensions.nesting import NestedState

NestedState.separator = '↦'

states = ['A', 'B',

{'name': 'C', 'children':['1', '2',

{'name': '3', 'children': ['a', 'b', 'c']}

]}

]

transitions = [

['reset', 'C', 'A'],

['reset', 'C↦2', 'C'] # overwriting parent reset

]

# we rely on auto transitions

machine = HierarchicalMachine(states=states, transitions=transitions, initial='A')

machine.to_B() # exit state A, enter state B

machine.to_C() # exit B, enter C

machine.to_C.s3.a() # enter C↦a; enter C↦3↦a;

machine.state

>>> 'C↦3↦a'

assert machine.is_C.s3.a()

machine.to('C↦2') # not interactive; exit C↦3↦a, exit C↦3, enter C↦2

machine.reset() # exit C↦2; reset C has been overwritten by C↦3

machine.state

>>> 'C'

machine.reset() # exit C, enter A

machine.state

>>> 'A'

# s.on_enter('C↦3↦a', 'callback_method')Instead of to_C_3_a() auto transition is called as to_C.s3.a(). If your substate starts with a digit, transitions adds a prefix 's' ('3' becomes 's3') to the auto transition FunctionWrapper to comply with the attribute naming scheme of Python.

If interactive completion is not required, to('C↦3↦a') can be called directly. Additionally, on_enter/exit_<<state name>> is replaced with on_enter/exit(state_name, callback). State checks can be conducted in a similar fashion. Instead of is_C_3_a(), the FunctionWrapper variant is_C.s3.a() can be used.

To check whether the current state is a substate of a specific state, is_state supports the keyword allow_substates:

machine.state

>>> 'C.2.a'

machine.is_C() # checks for specific states

>>> False

machine.is_C(allow_substates=True)

>>> True

assert machine.is_C.s2() is False

assert machine.is_C.s2(allow_substates=True) # FunctionWrapper support allow_substate as wellYou can use enumerations in HSMs as well but keep in mind that Enum are compared by value.

If you have a value more than once in a state tree those states cannot be distinguished.

states = [States.RED, States.YELLOW, {'name': States.GREEN, 'children': ['tick', 'tock']}]

states = ['A', {'name': 'B', 'children': states, 'initial': States.GREEN}, States.GREEN]

machine = HierarchicalMachine(states=states)

machine.to_B()

machine.is_GREEN() # returns True even though the actual state is B_GREENHierarchicalMachine has been rewritten from scratch to support parallel states and better isolation of nested states.

This involves some tweaks based on community feedback.

To get an idea of processing order and configuration have a look at the following example:

from transitions.extensions.nesting import HierarchicalMachine

import logging

states = ['A', 'B', {'name': 'C', 'parallel': [{'name': '1', 'children': ['a', 'b', 'c'], 'initial': 'a',

'transitions': [['go', 'a', 'b']]},

{'name': '2', 'children': ['x', 'y', 'z'], 'initial': 'z'}],

'transitions': [['go', '2_z', '2_x']]}]

transitions = [['reset', 'C_1_b', 'B']]

logging.basicConfig(level=logging.INFO)

machine = HierarchicalMachine(states=states, transitions=transitions, initial='A')

machine.to_C()

# INFO:transitions.extensions.nesting:Exited state A

# INFO:transitions.extensions.nesting:Entered state C

# INFO:transitions.extensions.nesting:Entered state C_1

# INFO:transitions.extensions.nesting:Entered state C_2

# INFO:transitions.extensions.nesting:Entered state C_1_a

# INFO:transitions.extensions.nesting:Entered state C_2_z

machine.go()

# INFO:transitions.extensions.nesting:Exited state C_1_a

# INFO:transitions.extensions.nesting:Entered state C_1_b

# INFO:transitions.extensions.nesting:Exited state C_2_z

# INFO:transitions.extensions.nesting:Entered state C_2_x

machine.reset()

# INFO:transitions.extensions.nesting:Exited state C_1_b

# INFO:transitions.extensions.nesting:Exited state C_2_x

# INFO:transitions.extensions.nesting:Exited state C_1

# INFO:transitions.extensions.nesting:Exited state C_2

# INFO:transitions.extensions.nesting:Exited state C

# INFO:transitions.extensions.nesting:Entered state BWhen using parallel instead of children, transitions will enter all states of the passed list at the same time.

Which substate to enter is defined by initial which should always point to a direct substate.

A novel feature is to define local transitions by passing the transitions keyword in a state definition.

The above defined transition ['go', 'a', 'b'] is only valid in C_1.

While you can reference substates as done in ['go', '2_z', '2_x'] you cannot reference parent states directly in locally defined transitions.

When a parent state is exited, its children will also be exited.

In addition to the processing order of transitions known from Machine where transitions are considered in the order they were added, HierarchicalMachine considers hierarchy as well.

Transitions defined in substates will be evaluated first (e.g. C_1_a is left before C_2_z) and transitions defined with wildcard * will (for now) only add transitions to root states (in this example A, B, C)

Starting with 0.8.0 nested states can be added directly and will issue the creation of parent states on-the-fly:

m = HierarchicalMachine(states=['A'], initial='A')

m.add_state('B_1_a')

m.to_B_1()

assert m.is_B(allow_substates=True)Experimental in 0.9.1:

You can make use of on_final callbacks either in states or on the HSM itself. Callbacks will be triggered if a) the state itself is tagged with final and has just been entered or b) all substates are considered final and at least one substate just entered a final state. In case of b) all parents will be considered final as well if condition b) holds true for them. This might be useful in cases where processing happens in parallel and your HSM or any parent state should be notified when all substates have reached a final state:

from transitions.extensions import HierarchicalMachine

from functools import partial

# We initialize this parallel HSM in state A:

# / X

# / / yI

# A -> B - Y - yII [final]

# Z - zI

# zII [final]

def final_event_raised(name):

print("{} is final!".format(name))

states = ['A', {'name': 'B', 'parallel': [{'name': 'X', 'final': True, 'on_final': partial(final_event_raised, 'X')},

{'name': 'Y', 'transitions': [['final_Y', 'yI', 'yII']],

'initial': 'yI',

'on_final': partial(final_event_raised, 'Y'),

'states':

['yI', {'name': 'yII', 'final': True}]

},

{'name': 'Z', 'transitions': [['final_Z', 'zI', 'zII']],

'initial': 'zI',

'on_final': partial(final_event_raised, 'Z'),

'states':

['zI', {'name': 'zII', 'final': True}]

},

],

"on_final": partial(final_event_raised, 'B')}]

machine = HierarchicalMachine(states=states, on_final=partial(final_event_raised, 'Machine'), initial='A')

# X will emit a final event right away

machine.to_B()

# >>> X is final!

print(machine.state)

# >>> ['B_X', 'B_Y_yI', 'B_Z_zI']

# Y's substate is final now and will trigger 'on_final' on Y

machine.final_Y()

# >>> Y is final!

print(machine.state)

# >>> ['B_X', 'B_Y_yII', 'B_Z_zI']

# Z's substate becomes final which also makes all children of B final and thus machine itself

machine.final_Z()

# >>> Z is final!

# >>> B is final!

# >>> Machine is final!Besides semantic order, nested states are very handy if you want to specify state machines for specific tasks and plan to reuse them.

Before 0.8.0, a HierarchicalMachine would not integrate the machine instance itself but the states and transitions by creating copies of them.

However, since 0.8.0 (Nested)State instances are just referenced which means changes in one machine's collection of states and events will influence the other machine instance. Models and their state will not be shared though.

Note that events and transitions are also copied by reference and will be shared by both instances if you do not use the remap keyword.

This change was done to be more in line with Machine which also uses passed State instances by reference.

count_states = ['1', '2', '3', 'done']

count_trans = [

['increase', '1', '2'],

['increase', '2', '3'],

['decrease', '3', '2'],

['decrease', '2', '1'],

['done', '3', 'done'],

['reset', '*', '1']

]

counter = HierarchicalMachine(states=count_states, transitions=count_trans, initial='1')

counter.increase() # love my counter

states = ['waiting', 'collecting', {'name': 'counting', 'children': counter}]

transitions = [

['collect', '*', 'collecting'],

['wait', '*', 'waiting'],

['count', 'collecting', 'counting']

]

collector = HierarchicalMachine(states=states, transitions=transitions, initial='waiting')

collector.collect() # collecting

collector.count() # let's see what we got; counting_1

collector.increase() # counting_2

collector.increase() # counting_3

collector.done() # collector.state == counting_done

collector.wait() # collector.state == waitingIf a HierarchicalMachine is passed with the children keyword, the initial state of this machine will be assigned to the new parent state.

In the above example we see that entering counting will also enter counting_1.

If this is undesired behaviour and the machine should rather halt in the parent state, the user can pass initial as False like {'name': 'counting', 'children': counter, 'initial': False}.

Sometimes you want such an embedded state collection to 'return' which means after it is done it should exit and transit to one of your super states.

To achieve this behaviour you can remap state transitions.

In the example above we would like the counter to return if the state done was reached.

This is done as follows:

states = ['waiting', 'collecting', {'name': 'counting', 'children': counter, 'remap': {'done': 'waiting'}}]

... # same as above

collector.increase() # counting_3

collector.done()

collector.state

>>> 'waiting' # be aware that 'counting_done' will be removed from the state machineAs mentioned above, using remap will copy events and transitions since they could not be valid in the original state machine.

If a reused state machine does not have a final state, you can of course add the transitions manually.

If 'counter' had no 'done' state, we could just add ['done', 'counter_3', 'waiting'] to achieve the same behaviour.

In cases where you want states and transitions to be copied by value rather than reference (for instance, if you want to keep the pre-0.8 behaviour) you can do so by creating a NestedState and assigning deep copies of the machine's events and states to it.

from transitions.extensions.nesting import NestedState

from copy import deepcopy

# ... configuring and creating counter

counting_state = NestedState(name="counting", initial='1')

counting_state.states = deepcopy(counter.states)

counting_state.events = deepcopy(counter.events)

states = ['waiting', 'collecting', counting_state]For complex state machines, sharing configurations rather than instantiated machines might be more feasible.

Especially since instantiated machines must be derived from HierarchicalMachine.

Such configurations can be stored and loaded easily via JSON or YAML (see the FAQ).

HierarchicalMachine allows defining substates either with the keyword children or states.

If both are present, only children will be considered.

counter_conf = {

'name': 'counting',

'states': ['1', '2', '3', 'done'],

'transitions': [

['increase', '1', '2'],

['increase', '2', '3'],

['decrease', '3', '2'],

['decrease', '2', '1'],

['done', '3', 'done'],

['reset', '*', '1']

],

'initial': '1'

}

collector_conf = {

'name': 'collector',

'states': ['waiting', 'collecting', counter_conf],

'transitions': [

['collect', '*', 'collecting'],

['wait', '*', 'waiting'],

['count', 'collecting', 'counting']

],

'initial': 'waiting'

}

collector = HierarchicalMachine(**collector_conf)

collector.collect()

collector.count()

collector.increase()

assert collector.is_counting_2()Additional Keywords:

title (optional): Sets the title of the generated image.show_conditions (default False): Shows conditions at transition edgesshow_auto_transitions (default False): Shows auto transitions in graphshow_state_attributes (default False): Show callbacks (enter, exit), tags and timeouts in graphTransitions can generate basic state diagrams displaying all valid transitions between states. The basic diagram support generates a mermaid state machine definition which can be used with mermaid's live editor, in markdown files in GitLab or GitHub and other web services. For instance, this code:

from transitions.extensions.diagrams import HierarchicalGraphMachine

import pyperclip

states = ['A', 'B', {'name': 'C',

'final': True,

'parallel': [{'name': '1', 'children': ['a', {"name": "b", "final": True}],

'initial': 'a',

'transitions': [['go', 'a', 'b']]},

{'name': '2', 'children': ['a', {"name": "b", "final": True}],

'initial': 'a',

'transitions': [['go', 'a', 'b']]}]}]

transitions = [['reset', 'C', 'A'], ["init", "A", "B"], ["do", "B", "C"]]

m = HierarchicalGraphMachine(states=states, transitions=transitions, initial="A", show_conditions=True,

title="Mermaid", graph_engine="mermaid", auto_transitions=False)

m.init()

pyperclip.copy(m.get_graph().draw(None)) # using pyperclip for convenience

print("Graph copied to clipboard!")Produces this diagram (check the document source to see the markdown notation):

---

Mermaid Graph

---

stateDiagram-v2

direction LR

classDef s_default fill:white,color:black

classDef s_inactive fill:white,color:black

classDef s_parallel color:black,fill:white

classDef s_active color:red,fill:darksalmon

classDef s_previous color:blue,fill:azure

state "A" as A

Class A s_previous

state "B" as B

Class B s_active

state "C" as C

C --> [*]

Class C s_default

state C {

state "1" as C_1

state C_1 {

[*] --> C_1_a

state "a" as C_1_a

state "b" as C_1_b

C_1_b --> [*]

}

--

state "2" as C_2

state C_2 {

[*] --> C_2_a

state "a" as C_2_a

state "b" as C_2_b

C_2_b --> [*]

}

}

C --> A: reset

A --> B: init

B --> C: do

C_1_a --> C_1_b: go

C_2_a --> C_2_b: go

[*] --> A

To use more sophisticated graphing functionality, you'll need to have graphviz and/or pygraphviz installed.

To generate graphs with the package graphviz, you need to install Graphviz manually or via a package manager.

sudo apt-get install graphviz graphviz-dev # Ubuntu and Debian

brew install graphviz # MacOS

conda install graphviz python-graphviz # (Ana)conda

Now you can install the actual Python packages

pip install graphviz pygraphviz # install graphviz and/or pygraphviz manually...

pip install transitions[diagrams] # ... or install transitions with 'diagrams' extras which currently depends on pygraphviz

Currently, GraphMachine will use pygraphviz when available and fall back to graphviz when pygraphviz cannot be

found.

If graphviz is not available either, mermaid will be used.

This can be overridden by passing graph_engine="graphviz" (or "mermaid") to the constructor.

Note that this default might change in the future and pygraphviz support may be dropped.

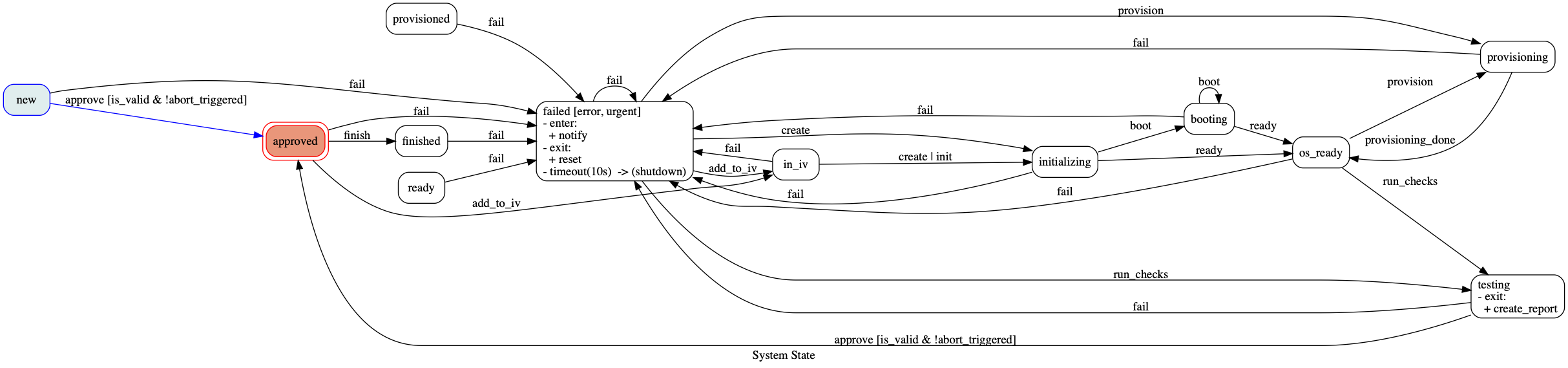

With Model.get_graph() you can get the current graph or the region of interest (roi) and draw it like this:

# import transitions

from transitions.extensions import GraphMachine

m = Model()

# without further arguments pygraphviz will be used

machine = GraphMachine(model=m, ...)

# when you want to use graphviz explicitly

machine = GraphMachine(model=m, graph_engine="graphviz", ...)

# in cases where auto transitions should be visible

machine = GraphMachine(model=m, show_auto_transitions=True, ...)

# draw the whole graph ...

m.get_graph().draw('my_state_diagram.png', prog='dot')

# ... or just the region of interest

# (previous state, active state and all reachable states)

roi = m.get_graph(show_roi=True).draw('my_state_diagram.png', prog='dot')This produces something like this:

Independent of the backend you use, the draw function also accepts a file descriptor or a binary stream as the first argument. If you set this parameter to None, the byte stream will be returned:

import io

with open('a_graph.png', 'bw') as f:

# you need to pass the format when you pass objects instead of filenames.

m.get_graph().draw(f, format="png", prog='dot')

# you can pass a (binary) stream too

b = io.BytesIO()

m.get_graph().draw(b, format="png", prog='dot')

# or just handle the binary string yourself

result = m.get_graph().draw(None, format="png", prog='dot')

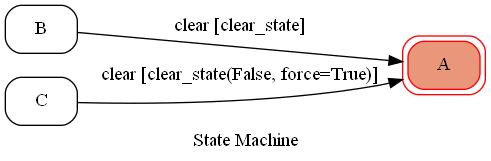

assert result == b.getvalue()References and partials passed as callbacks will be resolved as good as possible:

from transitions.extensions import GraphMachine

from functools import partial

class Model:

def clear_state(self, deep=False, force=False):

print("Clearing state ...")

return True

model = Model()

machine = GraphMachine(model=model, states=['A', 'B', 'C'],

transitions=[

{'trigger': 'clear', 'source': 'B', 'dest': 'A', 'conditions': model.clear_state},

{'trigger': 'clear', 'source': 'C', 'dest': 'A',

'conditions': partial(model.clear_state, False, force=True)},

],

initial='A', show_conditions=True)

model.get_graph().draw('my_state_diagram.png', prog='dot')This should produce something similar to this:

If the format of references does not suit your needs, you can override the static method GraphMachine.format_references. If you want to skip reference entirely, just let GraphMachine.format_references return None.

Also, have a look at our example IPython/Jupyter notebooks for a more detailed example about how to use and edit graphs.

In cases where event dispatching is done in threads, one can use either LockedMachine or LockedHierarchicalMachine where function access (!sic) is secured with reentrant locks.

This does not save you from corrupting your machine by tinkering with member variables of your model or state machine.

from transitions.extensions import LockedMachine

from threading import Thread

import time

states = ['A', 'B', 'C']

machine = LockedMachine(states=states, initial='A')