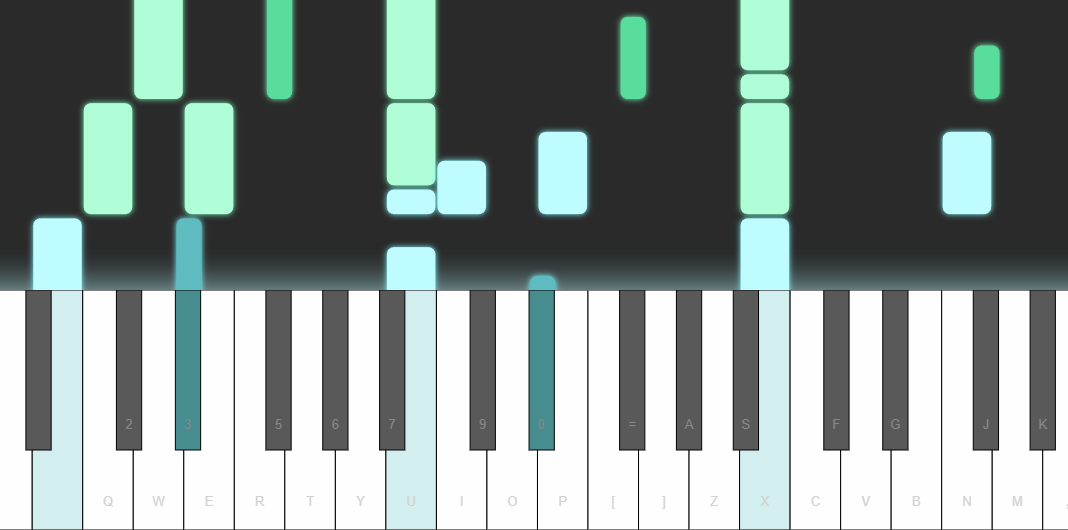

pianola is an application that plays AI-generated piano music. Users seed (i.e. "prompt") the AI model by playing notes on the keyboard, or choosing example snippets from classical pieces.

In this readme, we explain how the AI works and go into details about the model's architecture.

Music can be represented in many ways, ranging from raw audio waveforms to semi-structured MIDI standards. In pianola, we break up musical beats into regular, uniform intervals (e.g. sixteenth notes/semiquavers). Notes played within an interval are considered to belong to the same timestep, and a series of timesteps forms a sequence. Using the grid-based sequence as input, the AI model predicts the notes in the next timestep, which in turn is used as input for predicting the subsequent timestep in an autoregressive manner.

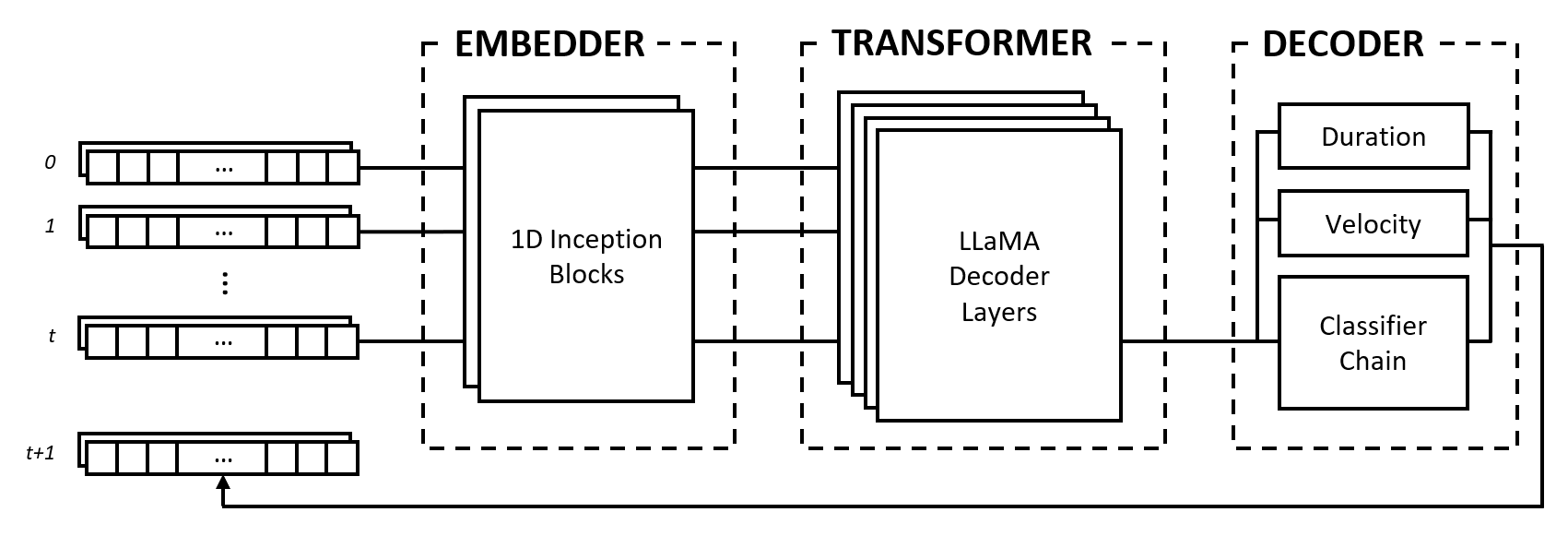

In addition to the notes to play, the model also predicts the duration (length of time the note is held down) and velocity (how hard a key is struck) of each note.

The model is made up of three modules: an embedder, a transformer, and a decoder. These modules borrow from well-known architectures such as Inception networks, LLaMA transformers, and multi-label classifier chains, but are adapted to work with musical data and combined in a novel approach.

The embedder converts each input timestep of shape (num_notes, num_features) into an embedding vector that can be fed into the transformer. However, unlike text embeddings which map one-hot vectors to another dimensional space, we provide an inductive bias by applying convolutional and pooling layers on the input. We do this for a number of reasons:

2^num_notes, where num_notes is 64 or 88 for short to normal pianos), therefore it is not possible to represent them as one-hot vectors.To allow the embedder to learn which distances are useful, we take inspiration from Inception networks and stack convolutions of varying kernel sizes.

The transformer module is comprised of LLaMA transformer layers that apply self-attention to the sequence of input embedding vectors.

Like many generative AI models, this module uses only the "decoder" part of the original Transformers model by Vaswani et al. (2017). We use the label "transformer" here to differentiate this module from the following one, which does the actual decoding of the states produced by the self-attention layers.

We choose the LLaMA architecture over other types of transformers primarily because it uses rotary positional embeddings (RoPE), which encodes relative positions with distance decay over timesteps. Given that we represent musical data as fixed intervals, the relative positions as well as distances between timesteps are important pieces of information that the transformer can explicitly use to understand and generate music with consistent rhythm.

The decoder takes in the attended states and predicts the notes to be played together with their durations and velocities. The module is made up of several subcomponents, namely a classifier chain for note prediction and multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) for feature predictions.

The classifier chain consists of num_notes binary classifiers, i.e. one for each key on a piano, to create a multi-label classifier. In order to leverage correlations between notes, the binary classifiers are chained together such that the outcome of prior notes affect the predictions for the following notes. For example, if there is a positive correlation between octave notes, an active lower note (e.g. C3) results in a higher probability for the higher note (e.g. C4) to be predicted. This is also beneficial in cases of negative correlations, where one might choose between two adjacent notes that results in either a major or minor scale (e.g. C-D-E vs C-D-Eb), but not both.

For computational efficiency, we limit the length of the chain to 12 links, i.e. one octave. Finally, a sampling decoding strategy is used to select notes relative to their prediction probabilities.

The duration and velocity features are treated as regression problems and are predicted using vanilla MLPs. While the features are predicted for every note, we use a custom loss function during training that only aggregates feature losses from active notes, similar to the loss function used in an image classification with localisation task.

Our choice to represent musical data as a grid has its advantages and disadvantages. We discuss these points by comparing it against the event-based vocabulary proposed by Oore et al. (2018), a highly cited contribution in music generation.

One of the main advantages of our approach is the decoupling of the micro and macro understanding of music, which leads to a clear separation of duties between the embedder and transformer. The former's role is to interpret the interaction of notes at a micro level, such as how the relative distances between notes form musical relations like chords, and the latter's task is to synthesise this information over the dimension of time to understand musical style at a macro level.

In contrast, an event-based representation places the entire burden on a sequence model to interpret one-hot tokens which could represent pitch, timing, or velocity, three distinct concepts. Huang et al. (2018) find that it is necessary to add a relative attention mechanism to their Transformer model in order to generate coherent continuations, which suggests that the model requires an inductive bias to perform well with this representation.

In a grid representation, the choice of the interval length is a trade-off between data fidelity and sparsity. A longer interval reduces the granularity of note timings, reducing musical expressivity and potentially compressing quick elements like trills and repeated notes. On the other hand, a shorter interval exponentially increases sparsity by introducing a lot of empty timesteps, which is a significant issue for Transformer models as they are constrained in sequence length.

In addition, musical data can be mapped to a grid either via the passage of time (1 timestep == X milliseconds) or as written in a score (1 timestep == 1 sixteenth note/semiquaver), each with its own trade-offs. An event-based representation avoids these issues altogether by specifying the passing of time as an event.

Despite its drawbacks, the grid representation has a practical advantage in that it is much easier to work with in the development of pianola. The model output is human readable and the number of timesteps corresponds to a fixed amount of time, making the development of new features much quicker.

Furthermore, research into extending sequence lengths of Transformer models and continued improvements to hardware will progressively reduce the problems caused by data sparsity, and as of late 2023 we are seeing large language models that can handle tens of thousands of tokens. As techniques get optimised and powerful hardware become more accessible, we believe that fidelity will continue to improve, just as it has done for image generation, leading to greater expressiveness and nuance in AI generated music.

The source code for this project is publicly visible for the purposes of academic research and knowledge sharing. All rights are retained by the creator(s) unless permissions have been explicitly granted.

Site icon modified from Freepik - Flaticon.

Get in touch on outlook.com at the address bruce <dot> ckc.